Mount Santubong In Sarawak Is a

Mite Tiny At Only 810m, But It Leaves You In No Doubt That It Deserves The

Epithet ‘Mountain’ Once You’ve Taken It On.

Occasionally, flights into or out of Kuching,

Sarawak, hover over the Santubong peninsula with its breath taking view of

forested coastline, shimmering rivers, and the unmistakable profile of a

dramatic and solitary limestone massif.

Some 35km from Kuching, the Santubong peninsula has

always been alluring for its strategic location and scenic beauty, even from

ancient times. The villages here continue a tradition hundreds of years old.

Excavations have unearthed evidence of settlements dating back to the 9th and

10th century AD.

Today, the Santubong peninsula and its surrounding beaches are literally a breath of fresh air for people from Kuching when they seek a break from the town life. A number of upmarket resorts line the beaches that fringe the peninsula, and there are idyllic fishing villages basking beside rivers or sheltering in little bays.

Today, the Santubong peninsula and its surrounding beaches are literally a breath of fresh air for people from Kuching when they seek a break from the town life. A number of upmarket resorts line the beaches that fringe the peninsula, and there are idyllic fishing villages basking beside rivers or sheltering in little bays.

Rustic seafood restaurants offer al fresco dining –

airy spaces, romantic views, the sound of waves lapping beneath wooden

platforms projecting out to sea and fresh seafood. The Sarawak Cultural

Village, a microcosm of Sarawak and the many native cultures that inhabit it,

nestle at the base of Gunung Santubong.

It hosts the wildly successful annual Rainforest WORLD Music Festival, a coming together of ethnic and folk musicians from around the WORLD for a few days every year in July. Despite development, the peninsula has maintained its elemental appeal. Estuarine shallows, a small human population and forested hinterland make bird-watching a good activity at the Buntal river estuary.

Wildlife can be occasionally spotted in the surrounding forests, and the rivers and shallow coastal seas host a number of the rare Irrawaddy dolphins, which can be seen on occasion by determined dolphin-watchers.

It hosts the wildly successful annual Rainforest WORLD Music Festival, a coming together of ethnic and folk musicians from around the WORLD for a few days every year in July. Despite development, the peninsula has maintained its elemental appeal. Estuarine shallows, a small human population and forested hinterland make bird-watching a good activity at the Buntal river estuary.

Wildlife can be occasionally spotted in the surrounding forests, and the rivers and shallow coastal seas host a number of the rare Irrawaddy dolphins, which can be seen on occasion by determined dolphin-watchers.

Dominating the Peninsula Is

Mount Santubong . . .

At only 810m above sea level, the salutation

“Gunung” or “mountain” seems ambitious, but this is no anonymous limestone

massif. Rising steeply and abruptly from forested lowlands to a peak that is

often shrouded in cloud, Gunung Santubong’s massive and rugged proportions

suggest mystery and power.

It completely dominates the peninsula, a glowering presence that is felt as much as seen. Up close, the massif, with its dripping thick vegetation, soaring rock walls and steep precipices, is massive and forbidding. Inevitably, it has spawned a legend, which involves – also inevitably – a celestial princess, the eponymous Puteri Santubong who came to grief and whose pregnant silhouette is today captured in the sinuous curves of the limestone mass.

There are a number of trails on Gunung Santubong, the Summit Trail being the one that leads to the peak. One of the resorts at its base maintains the trail, with trail markers, rope ladders and shelters. A self-guided hike can easily be accomplished, although guides can also be arranged.

One sunny morning, I set out with a couple of companions, carrying water, food, rain gear, flashlight, mobile phone, hat and good walking shoes. The trail, marked by a concrete archway, leads directly into and through a small wooden restaurant. Beyond, the wooden boardwalk continues into the rainforest.

It completely dominates the peninsula, a glowering presence that is felt as much as seen. Up close, the massif, with its dripping thick vegetation, soaring rock walls and steep precipices, is massive and forbidding. Inevitably, it has spawned a legend, which involves – also inevitably – a celestial princess, the eponymous Puteri Santubong who came to grief and whose pregnant silhouette is today captured in the sinuous curves of the limestone mass.

There are a number of trails on Gunung Santubong, the Summit Trail being the one that leads to the peak. One of the resorts at its base maintains the trail, with trail markers, rope ladders and shelters. A self-guided hike can easily be accomplished, although guides can also be arranged.

One sunny morning, I set out with a couple of companions, carrying water, food, rain gear, flashlight, mobile phone, hat and good walking shoes. The trail, marked by a concrete archway, leads directly into and through a small wooden restaurant. Beyond, the wooden boardwalk continues into the rainforest.

At this angle, Gunung Santubong

is said to look like an expectant Puteri Santubong

We met no other hikers

that morning; we had the forest seemingly to ourselves. The path is

well-defined, and there are signs on the trees to identify their species. This

is secondary lowland dipterocarp forest, which is relatively open and airy.

Once the sounds of the road have started to fade, you are greeted by the smells

and sounds which are at once familiar: the crystalline tinkling of water over a

boulder-strewn waterway, the dank smell of leafy decay, the dappled light from

broken foliage overhead, the rustle of dried leaves underfoot.

After an initially gentle stretch, the trail turned sharply and steeply to the left, presenting a long, unbroken stretch that scaled gloomy and silent heights. The trail, as ever, was clearly marked with ropes, and the mesh of gnarly roots helped with footholds. It was getting really quite steep, but in fact, it would get a lot steeper before we had sky overhead.

To the side of the trail, the forest and terrain fell sharply away; we were on the spine of a ridge, from which we could peer outwards to an aspect of meandering green rivers and forested lowlands under the uncertain shade of clouds. We had surprisingly ascended enough to obtain panoramic views of the surrounding countryside.

Eventually, awash in sweat in the humidity of the forest, we came to barren rock. The steep, large rock surfaces possessed an inscrutable presence, seemingly cloaked in a deep, solemn silence. It’s little wonder that many native peoples have superstitious beliefs regarding large rock formations.

Thankfully, there was a break in the dense foliage, allowing a waft of breeze in. We came to a rope ladder that had been strung over the steep rock surface. Beyond were more massive boulders, from which isolated tufts of vegetation sprouted, or gnarled and twisted trees wrested a foothold here and there. We were confronted with a picture of deep and terrifying isolation, which all the same offered an exhilarating escape from things civilised and cultured and ordered.

Ascending almost vertically upwards, it felt wonderful to be focused, to be using arms, hands, legs, shoulders to clamber slowly and surely up. We began to understand why, despite its seemingly diminutive height, trekkers sometimes had to be rescued from here. Up ahead, we heard voices, another group of hikers, one of whom was having a bit of difficulty.

They had a guide with them, and so we proceeded. (It later turned out that they had to be “rescued” as they were still stranded halfway up, or down the mountain, when it fell dark.) It became breezier as we ascended, and then we were in bright sunlight once again, and the rock beneath us was hot and there was blue sky above in which wisps of cloud drifted.

There was still a bit of a scramble before we reached the summit ridge, with its scrubby and low vegetation. A Stone Slab Marked the True Peak: 810m Above Sea level A shelter had been erected here, and all around were spectacular, shout-out-loud views of the surrounding land and coastline.

We could make out the resorts and golf course far below, the villages by the river, and the wake of boats out at sea. My 14-year-old climbing companion telephoned to tell his mother that he was at the top of Gunung Santubong. A hike, up and down, takes up the better part of a day.

The descent can be completed fairly rapidly, but it is taxing on the knees. For a mountain so accessible, Santubong is a challenging and satisfying hike. At the end of the hike, you are back at the wooden restaurant, when the desire for a cold drink and a good sit-down is top-most on your mind. In the background, Gunung – definitely gunung, and not bukit – Santubong glows a deep yellow in the late afternoon light.

Hike up to the top af Mt.

Santubong (840m) . . .

You will need approximately 3-4 hours to reach the

summit and around 2 hours to descend. If you plan to climb Mt. Santubong, the

best time to start is in the early morning. In the afternoon the peak might

become cloudy. The climb is really steep, especially when it is nearer to the

top.

In the beginning the path will lead you through the secondary rainforest; almost all the time you will be walking under the shade of the trees. Please note: The mountain is not that easy to climb.

Many people give up half way, every year there are cases where people got stranded and had to be rescued by helicopter. If you find it very challenging to climb to the summit, you may opt for easier jungle treks around the mountain first (see map).

In the beginning the path will lead you through the secondary rainforest; almost all the time you will be walking under the shade of the trees. Please note: The mountain is not that easy to climb.

Many people give up half way, every year there are cases where people got stranded and had to be rescued by helicopter. If you find it very challenging to climb to the summit, you may opt for easier jungle treks around the mountain first (see map).

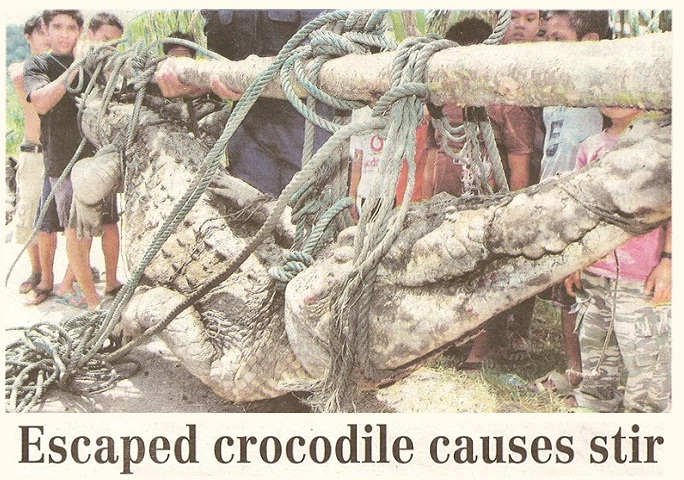

On

a slightly different scale, the local people at Santubong village (near

Kuching, Sarawak) found an unwelcome visitor in their front yard recently. This

is the village we anchor near when visiting Kuching, and we have heard of

crocodile attacks in the area in recent years. No, we don't swim there.